Leo Perutz: The Third Bullet

THE THIRD BULLET by Leo Perutz

Now and then a forgotten vanished day comes to mind. Then suddenly I see myself engaged in some foolish or barbaric deed, bereft of meaning or purpose, so I must puzzle over myself, must laugh, or even grow angry. My God, how did it happen that once upon a time, in a distant land, I murdered a king?

YET ANOTHER NEGLECTED WORK, BY AN UNDERRATED

WORLD-CLASS WRITER

Download the first part of my translation of The Third Bullet !

In the years between the great wars of the 20th century, Leo Perutz (1882-1957) was the most-read writer in German, admired, among others, by: J. L. Borges, Alfred Hitchcock, Graham Greene, Ian Fleming, Walter Benjamin, and Theodore Adorno.

In 1918, early in Perutz’ writing career, his friend Ernst Weiss commented:

… your book is of its kind, the most fabulous I’ve ever seen. I’m convinced that if you were an English or American writer, your work would be read in 100,000 copies from London to the Sudan. (Note 1)

A sentiment supported by Richard A. Bermann in 1923, when Perutz had two more novels and several stories under his belt:

If he were English, he would already be a Baronet, and swim in guineas. In the German lands he is still not much, just the best storyteller. Other novelists inhabit more exalted spheres, others again are more nimble with the typewriter, but none comes to mind as frequently as Leo Perutz, and no one else writing in German has such a full-blooded passion for storytelling. (Note 2)

In 1925 the pacifist journalist and publisher Carl von Ossietsky wrote:

In the Viennese writer Perutz there lurks an endless and uninterrupted delight in story-telling. He still feels a naïve pleasure in thinking up a fable, in the artifice involved in tangling and untangling the threads, in the impactful intermezzo, in the carefully prepared Grand Scene. He masters the mechanics of tension to the highest degree. He knows the reader’s secret wish: to be led through the labyrinth by an effortlessly reliable hand. He knows the itching for the next chapter, when at last, late in the night, the book has to be put aside. He fetches his themes from the realm of improbability, from that frontier region where the most powerful feats of imagination dwell so closely alongside the cheapest tricks of effect-making. (Here Balzac and Dostoyevsky were visitors; but Eugène Sue and Karl May were natives.) … The more romantically the plot develops, the more its colours glow. The more complicated the situation becomes, the more the characters come alive. The construction disappears behind the characters, the manipulating hand becomes invisible, the human being stands out. … (Note 3)

In January 1931 Ian Fleming wrote (in German) to Perutz:

In the last five years I have read the best and the worst of modern English, German, French and Russian literature, mostly untranslated, and have never once felt a need to write to the author.

Last Saturday I took “Little Apple” with me on a journey from Munich to London. From the yellow cover I mistakenly thought it one of those things one reads on a journey, where by page 37, after the police detective has been rendered thoroughly ridiculous, we know who murdered the rich American in his hotel room …

I finished your book in the early hours this morning, and I have to say I found it utterly gripping. I could write at length about the book: about the psychology, the continuity, and the Poe-like humanity of the whole thing – but my German is definitely not up to it. Not only that. This eternal theorising and criticising takes away dreadfully from spontaneity, and I shall only say that I admire your style, your language, and your art, down to the finest details. The word “genius” has through misuse long since lost value and meaning, otherwise I would simply define your book as a work of genius. (Note 4. Trans. CDG)

Fleming then notes with regret that Perutz remains almost unknown in the Anglophone world, and concludes: “I shall be pleased if, through the efforts of myself and my friends, you can achieve further successes.”

In the academic world of German literary criticism and history, Perutz was for half a century almost invisible. The 1,000 page Oxford Companion to German Literature (2nd ed. 1986) was unable to find space even for a mention.

Leo Perutz was born in Prague in 1882, and died in Austria in 1957. From 1938 to 1950 he was a reluctant exile in Palestine/Israel. By profession an “insurance-mathematical statistician” (in which role he published several papers), in October 1907 he joined the major insurance firm Assicurazioni Generale in (then-Austrian) Trieste: by sheer coincidence the same month when Franz Kafka joined the same firm in Prague! But Perutz apparently had little contact with the circle around Kafka and Max Brod. (Note 5) Vienna itself offered plenty of literary excitements in figures such as Karl Kraus and Arthur Schnitzler.

Between 1915 and 1936, Perutz published ten novels (two written in collaboration with his friend Paul Frank), as well as several short stories. In 1953 he published one further novel; and a novel found in his posthumous papers appeared in 1959. Not until the late 1980s/early 1990s were most of these dozen works republished in German. Of these, eight were translated into English.

THE THIRD BULLET

Perutz’ Anglophone publishers (Harvill/Harper Collins in the UK, Arcade in the US) somehow failed to commission a translation of his first novel: Die dritte Kugel (The Third Bullet), possibly because their enthusiasm had waned by the time the modern German reissue came out in 1993-94. My translation, the first part of which I am posting here, is the first into English.

(The other title passed over by the publishers – Zwischen Neun und Neun (Between Nine and Nine) – eventually appeared in English in 2010. If my translation of The Third Bullet can find a publisher, then all of Perutz’ sole-authorship titles will be available in English. That leaves only the two titles he co-authored with Paul Frank, and his short stories.)

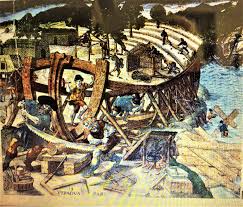

Written between 1911 and 1915 in several dozen notebooks, which he passed around to friends in batches for their comments – a practice Bermann chided as “highly crackpot”! (Note 6) – The Third Bullet is a historical thriller with elements of diabolism and magical realism. Alongside Hernando Cortez and King Montezuma, a colourful cast of German and Spanish desperados mingle and quarrel, in scene after scene of vivid action and dialogue.

Perutz’ language struck critics as recreating admirably the colloquial zest of Grimmelshausen, in Simplicius Simplicissimus, the marvellous 17th C. picaresque novel of the Thirty Years War; but, accepting his friends’ advice, Perutz toned down his use of antique spellings, and otherwise eschewed antiquarianist flummery.

The frame narrative set out in the Prologue poses questions of a life lived, a life remembered, and the meaning of it all.

MAJOR PUBLICATIONS BY LEO PERUTZ

(The translated titles can usually be found, reasonably priced, on www.abebooks.co.uk )

1915: Der Dritte Kugel (The Third Bullet) Untranslated until now. Setting is early 16th century in Germany and Mexico, featuring Cortez and Montezuma and magical realism.

1916: Das Mangobaumwunder (The Mango Tree Mystery, with Paul Frank). Untranslated. A macabre mystery involving exotic poisons and an enigmatic baron.

1918: Zwischen Neun und Neun (Between Nine and Nine). Trans. Thomas Ahrens & Edward Larkin, Ariadne Press 2010. A handcuffed prisoner jumps from a Vienna roof and spends a lively day evading capture – or does he? (A riff on the same trope as Ambrose Bierce’s An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.)

1920: Der Marques de Bolibar (The Marquis of Bolivar) . Trans. John Brownjohn, Arcade 1989. Intrigue and the unrolling of unintended but inevitable consequences during the Peninsular War in Spain.

1923: Der Meister des jüngsten Tages (The Master of the Day of Judgement). Trans Eric Mosbacher, Harvill 1994. Murder mystery set in early 20th C Vienna.

1924: Turlupin . Trans. John Brownjohn, Harvill 1996. Set in Cardinal Richelieu’s Paris, where curious events surround a momentous shuttlecocks tournament.

1924: Der Kosak und die Nachtigall (The Cossack ands the Nightingale, with Paul Frank). Untranslated. A burlesque love story involving an opera singer and the Russian husband she has left but who plots to ruin her romantic affairs.

1928: Wohin rollst du, Äpfelchen? (Little Apple). Trans. John Brownjohn, Arcade 1992. Set in Austria and Russia at the end of the First World War, this exciting adventure of thwarted vengeance ranks with All Quiet on the Western Front, published in the same year.

1933: SanktPetri-Schnee (Saint Peter’s Snow). Translated by Eric Mosbacher, Arcade, 1990. A coma, puzzling memories, mind-altering mildew: a feverish tale of a man caught between two realities.

1936: Der schwedische Reiter (The Swedish Cavalier). Trans. John Brownjohn, Arcade 1993. Set in the 17th C. Swedish-Polish wars, a nameless tramp assumes the identity of a Swedish officer, with fatal consequences.

1953: Nachts unter der steinernen Brücke (By Night under the Stone Bridge). Trans. Eric Mosbacher, Arcade 1990. An elegy for the lost world of Prague, set in the 16th C of mad Emperor Rudolf, the Jewish financier Mordechai Meisel, and the mystical Great Rabbi.

†1959: Das Judas der Leonardo (Leonardo’s Judas). Trans. Eric Mosbacher 1989. Milan in 1498: Leonardo is unable to finish his great painting of The Last Supper until he finds a suitable model for Judas.

In 1993 a volume of short stories written between 1907 and 1929 was published under the title Herr, erbarme Dich meiner (Lord have Mercy on Me).

NOTES

Materials for this introduction were found in the very useful volume Leo Perutz 1882-1957 (Vienna: Paul Zsolnay, 1989), compiled to accompany an exhibition at the Deutsche Bibliothek.